There are certain conditions which can be effectively managed and treated once their causes are understood, and trigeminal neuralgia is a particularly illustrative example of this.

Once it has been diagnosed and a patient has been referred to a radiotherapy centre for treatment, several pathways are available determined by a patient’s medical history and the cause of pain.

As understanding is important to the treatment and management of the condition, here are some facts about trigeminal neuralgia that are important to know.

A Dentist Will Often Notice Symptoms First

The facial pain caused by trigeminal neuralgia is often felt in the gums, jaw and teeth, which usually means that it will be a dentist who will be the first person that many patients see when seeking treatment for the condition.

They can rule out that it is a toothache, abscess, or other dental concern through the use of an X-ray or dental CT scan, before suggesting that the patient sees their GP, who will themselves help to rule out other conditions that could cause similar pain sensations.

Once other causes are ruled out, a GP will refer the patient to a specialist or the patient will seek out a second opinion.

It Was First Discovered Three Centuries Ago

Trigeminal neuralgia is sometimes known as Fothergill disease, named after the doctor who first discovered the condition, John Fothergill.

In 1773, Dr Fothergill provided the first complete and accurate description of the condition, and would also describe conditions such as angina, diphtheria and streptococcal sore throat in English for the first time.

Nearly a century later, another doctor for the University of Edinburgh, John Murray Cornochan, would be the first person to successfully treat trigeminal neuralgia, through a surgical procedure to remove the trigeminal nerve.

There Are Three Main Types Of Trigeminal Neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia cases are grouped into three categories depending on the cause.

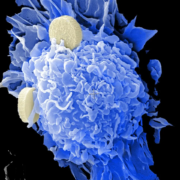

The first, and most common of these, is known as classical trigeminal neuralgia, which is caused by pressure on the trigeminal nerve which makes it activate and causes the facial pain that is characteristic of the disorder.

If the trigeminal neuralgia symptoms are caused by another medical condition, such as a tumour, multiple sclerosis or injury to the face, it is categorised as secondary trigeminal neuralgia.

Finally, if the cause is unknown, it is categorised as idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia, and until a cause is determined, treatment is centred around pain management.

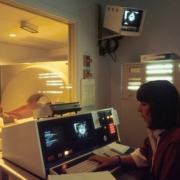

MRI Scans Can Find The Cause

In most cases, a diagnosis is confirmed through a magnetic resource imaging (MRI) scan, which uses a series of magnetic fields to create a detailed internal image of the face.

It can be used to find pressure on the trigeminal nerve, its location and the precise cause. This can be used to diagnose a patient’s symptoms as trigeminal neuralgia and is typically used to help plan treatment.

It Does Not Always Require Surgery To Treat

There are three main treatment paths, depending on the cause and how well a patient has responded to other treatments.

Initially, anticonvulsant medication is the first treatment many people with trigeminal neuralgia are likely to take.

Many over-the-counter painkillers are not effective at treating the specific cause of pain seen with trigeminal neuralgia, so regular doses of an anticonvulsant medication such as carbamazepine will be initially taken to slow down nerve impulses and stop the trigeminal nerve from activating.

Alternative medicines are available if carbamazepine does not work, but specialist surgery can also be offered which can provide relief for months, and sometimes years.

This includes microvascular decompression, which helps relieve pressure on the trigeminal nerve and can therefore provide long-term pain relief.

These also include keyhole surgical treatments undertaken under general anaesthetic which aim to deactivate the nerve entirely, but an alternative to this that specialists are using to treat trigeminal neuralgia without the need for surgery is stereotactic radiosurgery.

Treatments such as Gamma Knife work by using multiple beams of radiation concentrated to a point to provide precise doses of radiation to damage the trigeminal nerve where it enters the brainstem.

It works through the use of a complex frame which holds your head in place and is used to guide the beams of radiation to the central point where the nerve needs to be damaged in order to stop activating.

It requires no incision, no general anaesthetic (although local anaesthetic is often provided for the points where the frame is secured), and does not require a stay in the hospital once the procedure is completed.

It can sometimes take time for the procedure to take effect, but it can provide relief for years.