Radiation Oncology specialist, Dr. Kuczer

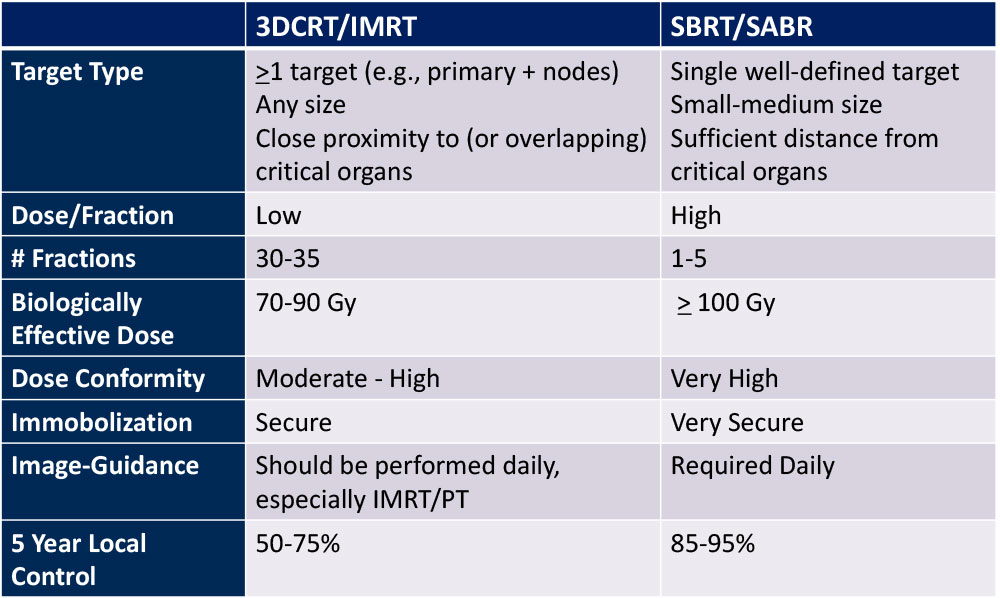

3D-CRT vs. SBRT

Respiratory Motion Management

Conventional (ITV-based)

– Contour and treat full tumor ROM

Accelerator beam gating

– Patient breathes normally; beam only on while patient is in a certain phase of the respiratory cycle

Active breathing control

– Patient holds breath in a certain position; beam only on in that phase of the respiratory cycle

Dynamic tumor tracking

– Patient breathes normally; tumor is tracked; beam always on and moves with tumor

Regardless of the motion management used, an additional “CTV/PTV” margin around our target is needed to ensure that we hit it.

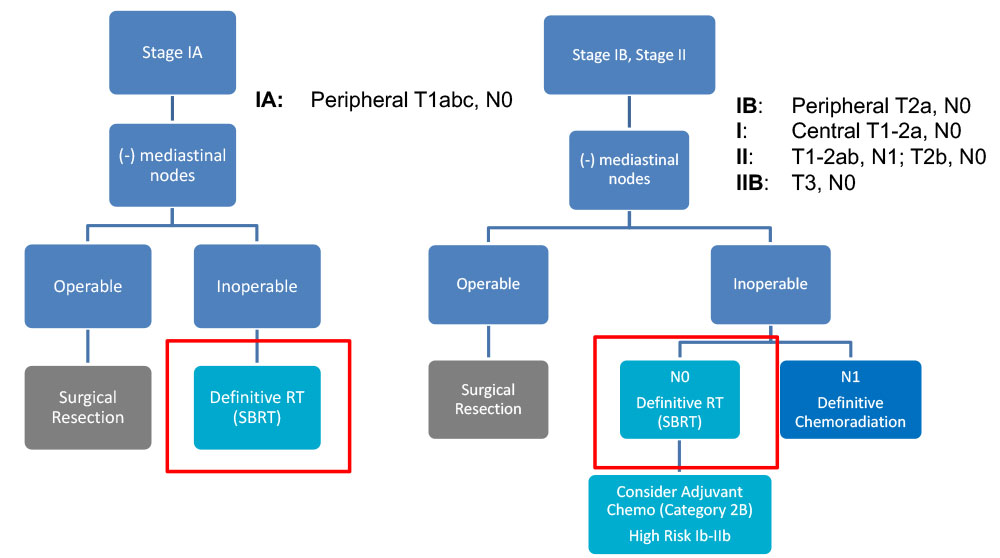

Curative Indication - NCCN Guidelines – NSCLC

Curative Indication - NCCN Guidelines – NSCLC

- Surgical resection is the preferred local treatment

– An anatomical resection with lobectomy or segmentectomy is preferred to wedge resection

– Includes sampling of at-risk ipsilateral hilar and mediastinal LN

- SBRT for patients who are medically inoperable or refuse surgery

–Limitations: High volume (DM > 5cm) and “ultra-central” tumors should be treated more cautiously (e.g. 10 instead of 3 fractions)

–Limited data yet supporting the addition of systemic therapy to SBRT

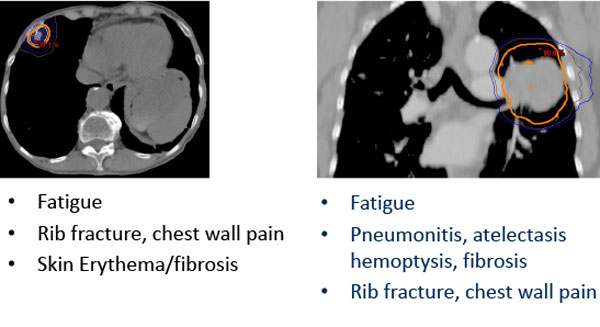

Potential SBRT Toxicity Depends on Tumor Site

Risk of toxicity can be reduced through risk-adapted dose-fractionation

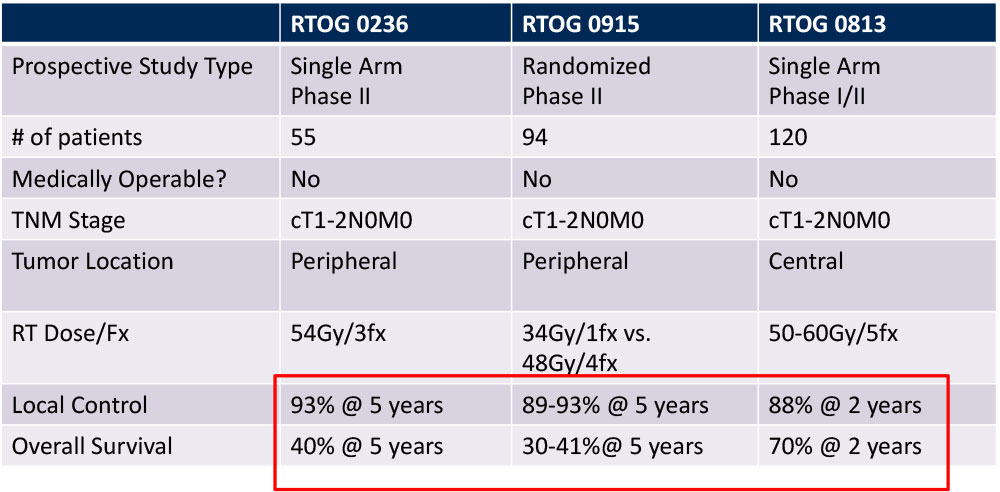

Outcomes of SBRT for Early Stage NSCLC

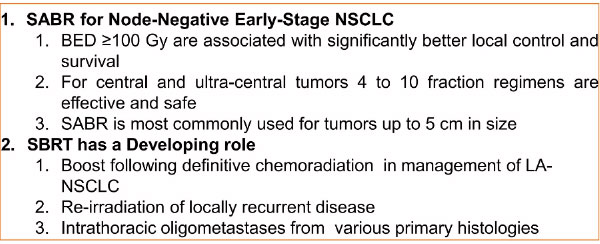

Take Home Pearl and Further Indications of SBRT for NSCLC

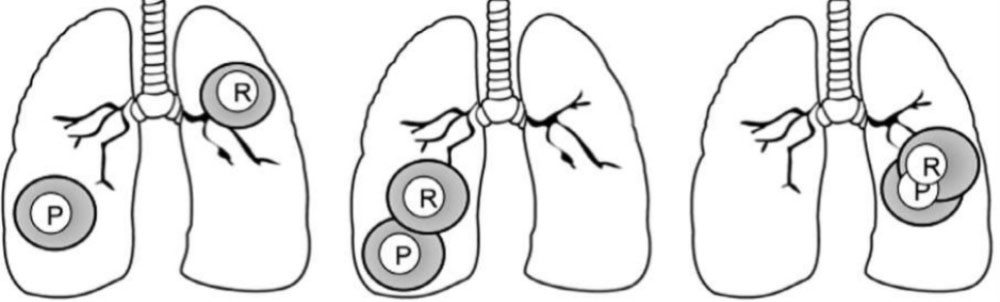

Reirradiation of Recurrent disease

- Feasibility of treating with curative intent depends on site of primary (P) and recurrent (R) tumors

- Advanced treatment techniques are particularly useful for sparing normal tissue (e.g., IMRT, SBRT, protons)

– Reirradiating central structures (e.g., esophagus, airway) most challenging

– Long-term toxicity is the major concern – impacted by dose/fraction

SBRT in the Management of Stage IV NSCLC

Palliative Radiation For Symptom Relief

- Pain

–Bone metastases

- Neurologic symptoms

–Spinal cord compression

–Brain metastases

- Bleeding

–Endobronchial tumor

- Dyspnea/Dysphagia

–Tumor obstruction causing SVC, respiratory distress or esophageal narrowing

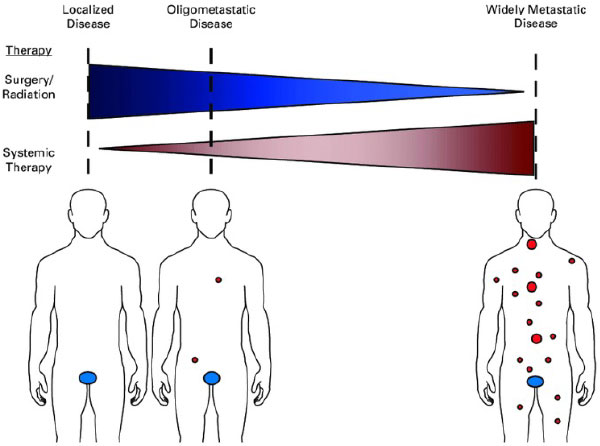

Is all metastatic disease the same?

- No! Lung cancer has M1a, M1b and M1c designations because the metastatic state at diagnosis impacts prognosis; a small subset of patients may be cured

- “Oligometastatic” refers to a situation where distant metastases may be limited in number (typically defined as < 5 mets in < 3 organs), and potentially curative treatment can be delivered prior to the development of widespread disease

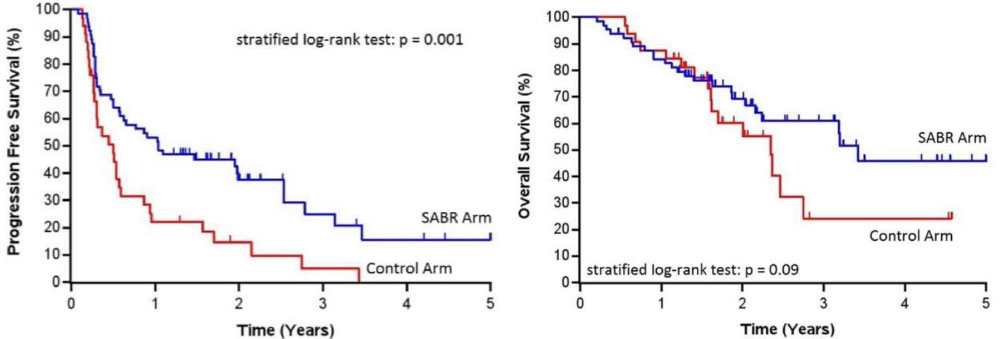

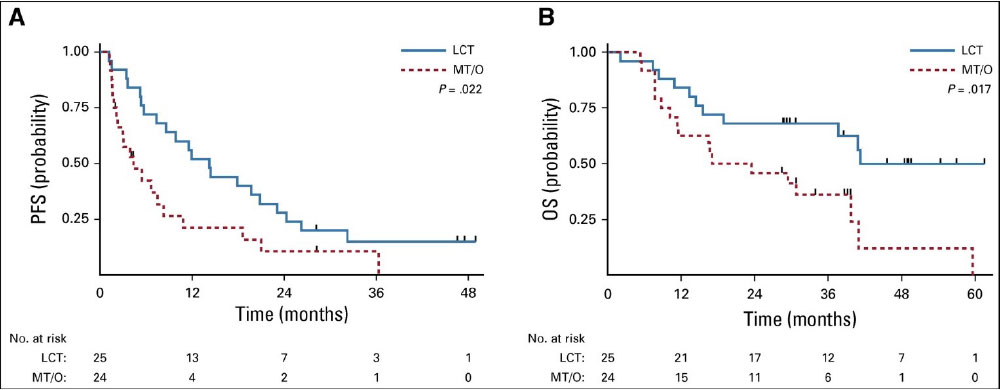

UT Southwestern Randomized Phase II Trial

- Iyengar et al, JAMA Oncol, 2018

- 29 patients, oligometastatic NSCLC with < 5 sites of disease (EGFR/ALK negative), PR or SD after induction chemo, randomized to +/- SAbR

- SAbR à ↑ M-PFS (3.5à9.7mo)

SABR-COMET Randomized Phase II Trial

- Palma et al, Lancet, 2019

- 99 patients, variety of oligometastatic cancers with < 5 sites of disease, PR/SD on systemic therapy, randomized 1:2 to +/- SAbR (at ablative doses)

– Most common histologies: breast, lung, colorectal, prostate - SAbR à ↑ M-PFS (6à12mo, p<0.001) & M-OS (28à41mo, p=0.09)

– Also ↑ G2 or higher toxicity, but no difference in QOL

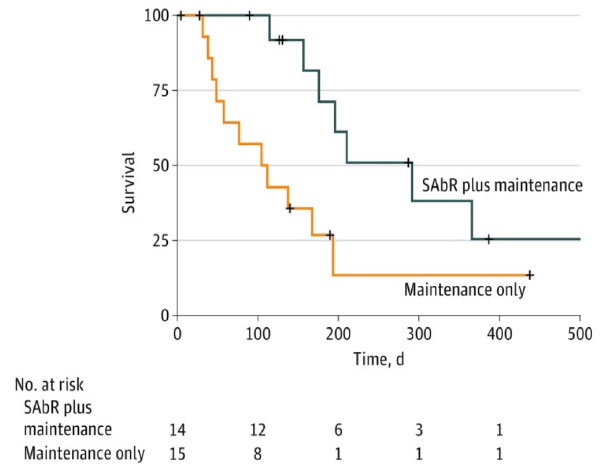

Multi-Institutional Randomized Phase II Trial

- Gomez et al, J Clin Oncol, 2019

- 49 patients with oligometastatic NSCLC with < 3 sites of disease, SD/PR after Pt-based doublet or EGFR/ALK inhibitor, randomized to maintenance systemic therapy +/- local consolidative surgery/RT

- RT à ↑ M-PFS (4.4à14.2mo) and M-OS (17à41mo, p=0.02)

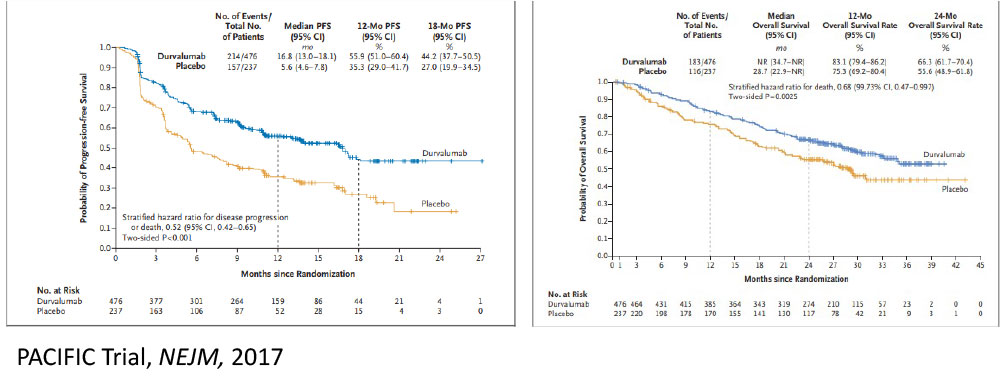

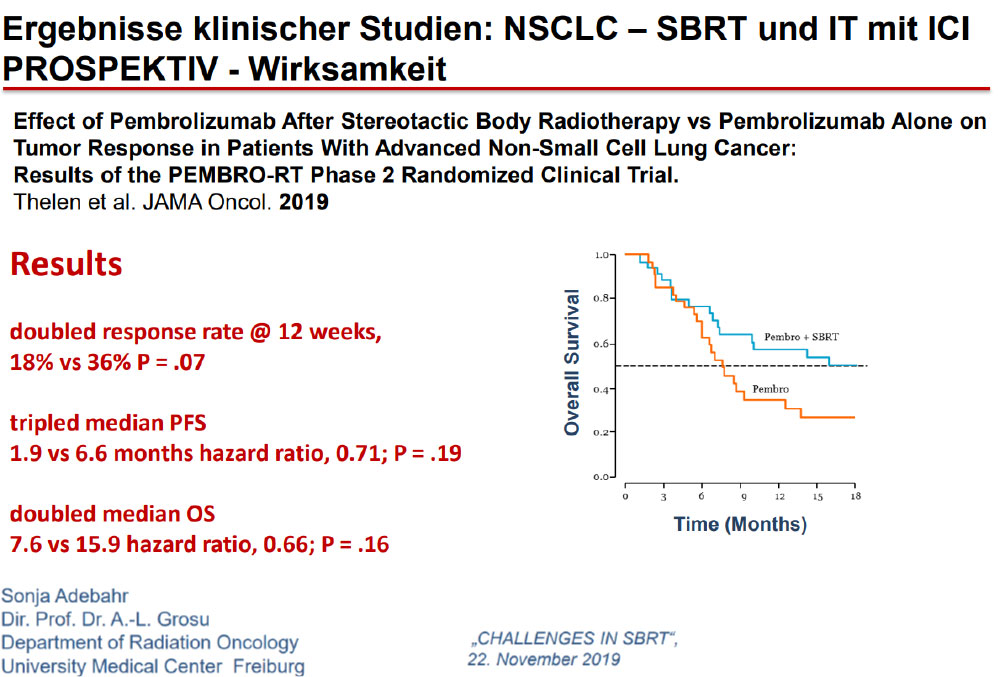

The Future…

Immunotherapy May Change Our Approach to Locoregional Management Too

A stronger immune response may be elicited by leaving a tumor in and irradiating it, rather than removing the largest source of antigenic stimulation.

The Future……Aktive Protokolle

PACIFIC-4 / RTOG 3515

Inclusion Criteria

- Clinical Stage I/II node negative (T1 – T3 N0)

- Medically inoperable or refuse surgery

- ECOG PS 0-2

- All comers for histology and PDL-1 status

- Sync/Metach allowed

The Future…A Few Examples of Active Clinical Trials in Lung Cancer

CAVE: Not all new substances proofed to be safe with SBRT. Additional surveys needed!

- NRG LU002: Adds RT (to all sites of disease) to systemic therapy for oligometastatic NSCLC

- NRG LU004: Adds immunotherapy to IMRT or 3-D CRT for stage II-III NSCLC with high PD-L1 expression (instead of chemotherapy)

- PACIFIC 4 and NRG/S1914: Adds consolidative immunotherapy to SBRT for stage I NSCLC

- AEGEAN: Adds neoadjuvant immunotherapy to surgery for resectable stage II-III NSCLC

- ALCHEMIST: Evaluating adjuvant use of targeted agents for resected NSCLC

- RTOG 1308: Compares proton therapy to photon therapy for LA-NSCLC

- NRG LU005: Adds immunotherapy to chemoradiation for limited-stage SCLC

- NRG CC003: Hippocampal avoidance PCI for SCLC

Quellen

- David S. Buchberger et al. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for the Management of Early-Stage Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Clinical Overview. JCO Oncol Pract 19, 239-249(2023).DOI:10.1200/OP.22.00475

- DrAyush GargRole of SBRT in lung cancer 8. Okt. 2019•, A topic with precide information regarding role of SBRT in Lung Cancer, https://de.slideshare.net/DrAyushGarg/role-of-sbrt-in-lung-cancer

- Kanhu Charan LUNG SBRT A LITERATURE REVIEW 27. Feb. 2023, https://de.slideshare.net/kanhucpatro/lung-sbrt-a-literature-review

SBRT bei NSCLC

VIELEN DANK!