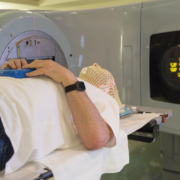

The initial steps following a diagnosis of cancer can be quite disconcerting, and it is understandable to feel confused and worried in that space between receiving the confirmation through a series of tests and examinations and your first session of radiotherapy.

At our international cancer care centre, you will be taken care of by a team of specialists, all of whom will be able to provide specific treatments and specialist advice in their fields of expertise, as well as work together to provide a comprehensive treatment plan.

As we have a major focus on patient-centred care, your needs will be at the heart of every care decision we make, and we will be happy to answer any questions and discuss any aspect of treatment you need. Ultimately, the decision to start radiotherapy or chemotherapy is yours to take.

Before you do, we have three simple but broad questions we recommend that you ask your multidisciplinary cancer team in order to provide greater insight and understanding of your treatment and ensure that the team’s recommendations align with your treatment goals as a patient.

What Is The Ultimate Goal Of Treatment?

Because there are so many types of cancer, there are a lot of different types of treatment, each of which can vary depending on the stage of cancer, the overall health of the person, how aggressive the cancer is and many other aspects.

However, one question to ask about every part of your treatment is what the goal of the particular intervention is.

On a broad level, the goal of treatment is typically to remove the cancer or reduce it to a level where it can no longer be found in the body, but this may not always be the case.

Sometimes, radiotherapy is used as an adjunctive treatment to help shrink a tumour to make surgery more viable and shorten long-term recovery; in other cases, it is used with chemotherapy to make both more effective, and in some cases, it is used to ensure the last remnants of cancer cells are destroyed and thus cannot grow back.

In other cases, the goal of radiotherapy is to relieve pain, particularly in cases where a particular tumour might be inoperable. Sometimes shrinking a tumour can be enough, at least in the short term, to relieve symptoms before alternative steps of treatment can be considered.

As suggested above, every treatment intervention will have a specific purpose that helps forward an overall goal, and asking what each part of the treatment does will aid in understanding what will happen in the future.

What Are The Effects Of Treatment And How Will They be Managed?

Depending on when a cancer is diagnosed, the treatment may be somewhat aggressive, which can lead to some additional symptoms that it is important to understand ahead of time.

Not every cancer treatment will have side effects; if a tumour is caught quickly enough and is eliminated through a short course of radiotherapy, you may barely notice the treatments at all.

In other cases, as cancer treatment typically relies on the body’s ability to regenerate and recover, symptoms such as fatigue, aches and pains are not uncommon, and other types of treatment will have specific symptoms that may need to be managed as part of your complete package of care.

This is why a cancer team consists of specialists from all aspects of the medical profession, from radiologists to physiotherapists.

They will help ensure that treatment is as minimally invasive as possible, has as few side effects as possible and will help ensure that your mental and physical health is at the best possible level to encourage the best possible outcomes.

Asking about these interventions will help to tailor your treatment plan around your needs and ensure that your stay at our cancer clinic will provide you with the best possible care.

Why Choose Radiotherapy And What Are The Alternatives?

This is technically two different questions, but they both focus on the same fundamental point; why did the cancer team come to the conclusion that the treatment they suggested is the most effective treatment for someone in the long term?

In many cases, the best way to ask this question is to ask about alternative treatments as well. Many cancers can be treated in multiple ways depending on the stage of treatment and the expected outcome.

There are various considerations made and weighted differently, and knowing what alternatives are available will give you the chance to make an informed decision that puts your needs at the forefront of your care, where they belong.